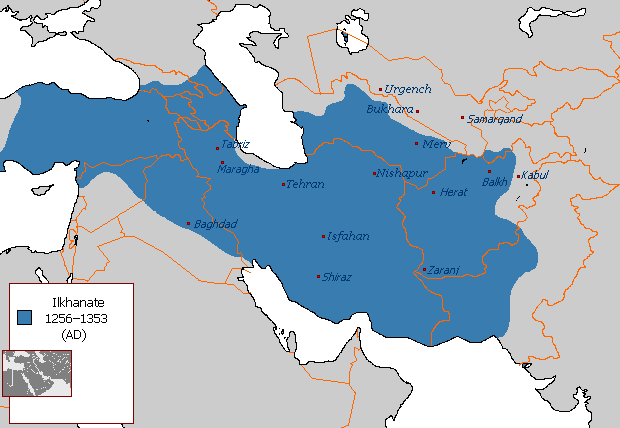

In 1258, the Mongol Ilkhanate invaded the Caliphate and ransacked the capital for 13 days, an event which we now remember as the Siege of Baghdad. They murdered the Abbasid Caliph Al-Musta’sim while imprisoning members of the Abbasid ruling family. The Mongols didn’t stop there, continuing west to Egypt and Syria. Under these conditions, the Caliphate was under siege and in a state of emergency.

Some people rightly raise the question as to what happened to the continuity of the Caliphate given this predicament. Especially in the context of the oft-repeated comment that “the Caliphate continued for almost 1.5 millennia”, this notion is worth exploring with an inquisitive lens.

It is worth noting in this regard the following hadith. Ibn Habban and Ibn Majah narrated from Ibn ‘Abbas:

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said, ‘Allah has forgiven my Ummah for their mistakes and forgetfulness and that which they were compelled to do.’

The Sultans (leaders) of certain regions, who were responsible for their own Wilayahs and who would run these almost independently of the Khalifah, were not of Qureyshi descent. This meant they couldn’t be Caliphs according to the prevailing juristic opinion at that time. While this is not the only opinion on the issue (and indeed Hizb ut-Tahrir adopts a different opinion) it was the one that was adopted at the time. Specifically, and of relevant note here, the rulers of Egypt were Berbers.

Nonetheless, and after 2-3 years of Muslims being ruled by the Mongols, Sultan Saiful Deen Al Qutuz of Egypt (the 4th Sultan of the Berbers that ruled Egypt) won a decisive victory against the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jaloot in 1260 and halted their advance.

Following this, members of the Abbasid family were released from prison in Baghdad, among whom was the son of the previous Abbasid Caliph Az-Zahir. He then fled to Cairo where he presented himself to the ruling Berbers. The Chief Qadi (judge) in Cairo verified that he was from the ruling Abbasid family (and thus a Qureyshi) and the Berbers gave him the bay’ah in 1261. Ulema such as the great Imam ‘Izz Al Deen Ibn Abdul Salam also gave their pledge to Mustansir Billah.

The Abbasid Caliphate lasted from 750 to 1258, then resumed in 1261 under the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt

In analysing this situation, it is clear that Muslims of the time found themselves in an emergency and one in which they were compelled with regards to the political situation that prevailed over them. In this context, there can be no “blame” in the strict sense attributed to either the public or influentials of the time. The devastation of the Mongol invasion, known for its ferocity, also created a panic that the ummah has seldom known – the predictions that the Day of Judgement were nigh were widespread due to the sheer terror that people were confronted with and the wanton brutality of the Mongol invaders.

The situation where a period of time passed without a Caliph being legitimately contracted by the ummah was not without precedent. According to strong scholarly opinions (though not necessarily a unanimous view), the period of Yazid’s rule 6 centuries earlier was one in which the bay’ah had not been validly contracted, meaning that the ummah was without a validly contracted Caliph for almost 4 years. Yet there, given the pressure under which this bay’ah was possibly effected and with the difficulty of the prevalent political situation, it is impossible to exact blame upon influentials or the ummah. As such, the lack of a validly contracted Caliph (according to that particular opinion) falls under the ambit of compulsion which the ummah faced at the time.

The situation that faced the Muslims at the time of the Mongol invasion was not dissimilar in regard to the compelling situation that confronted the ummah earlier.

However, the key point to note is that the lack of a contracted Caliph was not by design, neglect or anything similar; it was rather the result of a peculiar political reality forced upon the Muslims of the time by an unprecedented invasion.

Notably, while the Caliph as a leader was not validly contracted, the major components of what was the Caliphate still existed and continued to operate, including judges throughout the areas, the existence of provinces ruled by various Sultans (as mentioned above), and so forth.

Genghis Khan’s grandson Berke Khan had earlier converted to Islam in 1252, several years prior to the invasion. He was outraged at Hulagu attacking Baghdad and he pursued and defeated Hulagu in 1263. Eventually, large segments of the Mongols (or Tatars as they are also known) came to accept Islam.

![]()