By Shafiul Huq*

The idea of the irrelevance of the Caliphate as a governmental model in the modern world is not altogether new. It has been raised by several writers over the past few years and came into sharp focus as a result of the (false) proclamation of a Caliphate by ISIL in 2014. While the legitimacy of ISIL’s claim has been repudiated by Muslims all over the world, this thesis itself is worth interrogating for the broader claims it makes.

In an article titled “Why the New Caliphate is Irrelevant,” Akhilesh Pillalamarri of The Diplomat raised some issues regarding the existence and relevance of the Caliphate, both historically and as a model in the the modern world. Pillalamarri represents a commonly held outsider skepticism and misunderstanding of what the Khilafah really is; especially as Muslims understand from our religious texts, so we seek here to briefly address some of those points by providing a different perspective on how we understand the Caliphate and the call for its return.

Pillalamarri says regarding the Caliphate that “…the concept has been superfluous throughout most of history,” and that, “The universal Caliphate is a pipe dream.” This contention appears to be based on the premise that schisms have existed amongst different factions within the Caliphate, and that there have often been multiple claims to the position of the Caliph.

These claims assume that because of the political problems that existed at the time of certain Caliphates, the Caliphate as envisioned by Muslims who call for its return has never been a reality in Islamic history, but rather a “superfluous” concept.

By casually dismissing the Caliphate as a romantic ideal, the article oversimplifies, in fact completely misrepresents, how the Caliphate is understood in Islamic thought and how it was a central feature of Islamic civilization for centuries.

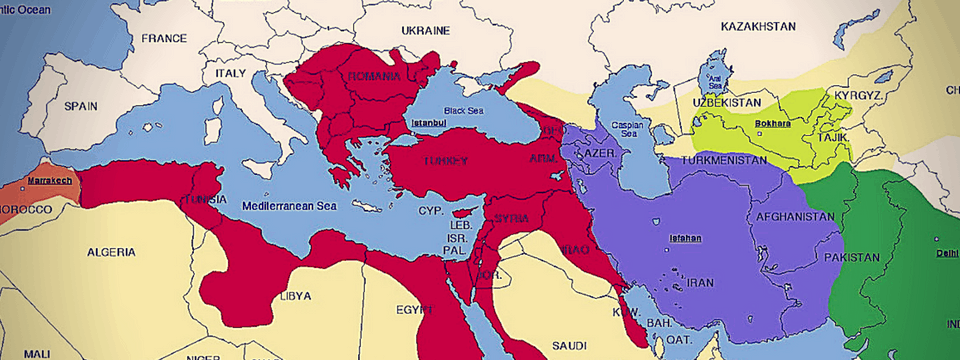

Topkapi Palace (Istanbul) was the seat of the Caliphate for several centuries, which was given its authority from principled readings of the primary religious texts.

For Muslims, the Caliphate is not just another “empire” that existed during a certain period of history. Rather, Muslims consider its establishment a divine command because it is the institution through which Muslims implement divine laws in society and convey the call to Islam to the rest of the world. Therefore, contrary to the author’s claim, the Caliphate is essential to the religious practice of Muslims, and Islamic scholars throughout the centuries have discussed this issue at length.

From this perspective, the Caliphate is the general leadership of Muslims responsible for the implementation of Islamic law, the Shari’ah. The implementation of the Shari’ah means that the laws adopted and implemented are based on the primary Islamic texts – the Qur’an and the Sunnah (tradition) of the Prophet Muhammad (may peace be upon him) – and have been derived through an Islamically valid legal methodology.

Muslims, like many other civilizations, have experienced ups and downs. There has been infighting, political turmoil, multiple claims to the seat of the Caliph and all the other problems that civilizations normally face. Yet despite these challenges, for almost 1300 years, the Qur’an and the Sunnah have remained the primary sources of law for Muslims.

Related: Classical scholars on the obligation of the Caliphate.

There were no doubt misapplications of the Shari’ah by certain rulers, yet there was never a blatant rejection of the primary Islamic texts as the only sources of law, nor was there ever an explicit reference to foreign sources for legislative purposes.

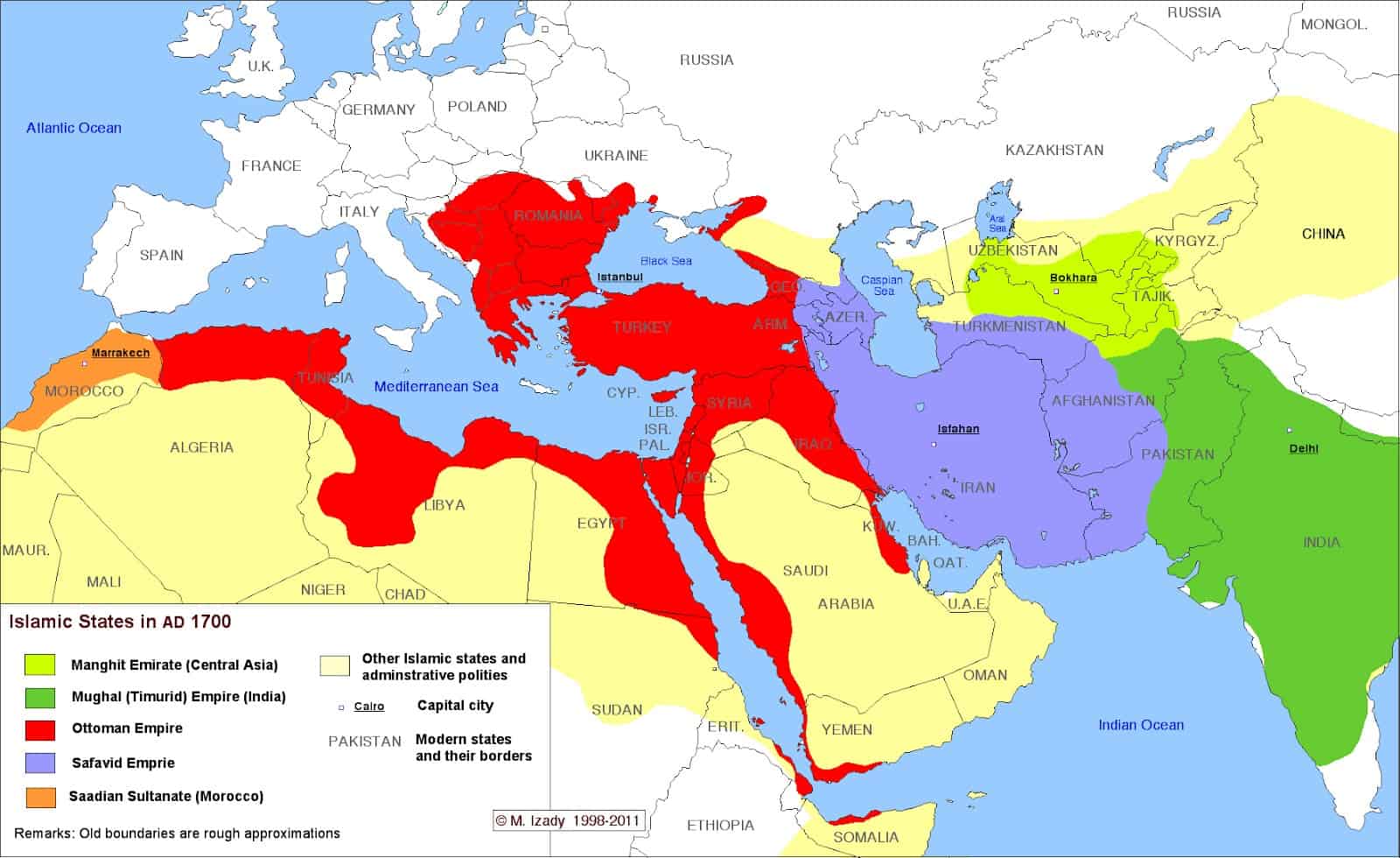

There were autonomous regions, such as the Indian subcontinent, but those Muslims nevertheless identified themselves as being part of a global Ummah (community of Muslims). In fact, despite being administratively autonomous, the different dynasties ruling over India derived their legitimacy from the Caliph at the time, whether during the Abbasid or the Ottoman era. The Caliphate was thus not merely a pipe dream, but a lived reality for Muslims, and an essential aspect of their civilization.

This is in stark contrast to today in the Muslim lands where Muslim countries are divided according to the model of the modern nation state, a product of European colonialism, and their systems of governance are either monarchic, autocratic, or secular-democratic.

Despite some countries attempting or purporting to govern according to semblance of Islamic law, such as Saudi Arabia or Iran, their legislation is not derived from Islamic sources primarily and at best a bit-part patchwork of foreign civil codes interspersed with elements of Shar’iah here and there. Whatever aspect of the Shari’ah is implemented in these countries, they are usually chosen based on convenience rather than a rigorous jurisprudential process.

Some Muslim lands were autonomous provinces that were well suited to conduct their affairs when the need arose while still owing their allegiance to the Caliph. Self-standing, modern nation states (seen in the national borders) were superimposed much later, and are unable to address the problems we see today.

Modernity’s imposition on Muslims of systems and values alien to their beliefs, and the changing of their traditional way of life – where Islamic laws and values were the lifeblood of society – have left Islamic lands in turmoil. Notwithstanding this, there are clear trends and evidence for Muslims being intent on returning to their traditions.

This aspiration is not a utopian dream. It is not to ignore “the natural tendency in human nature for schism.” Neither is it a false delusion that problems will not exist in the Caliphate. Rather, it is to call for a different set of solutions to the problems faced by humans: solutions that are in line with the beliefs and values of Muslims, instead of models forcibly imposed by foreign sources.

Islamic thought provides a unique perspective towards life’s important questions and Islamic jurisprudence is rich and robust enough to provide legal answers to new questions that may arise with the progress of time. The call for a Caliphate is thus a call to organise society on this basis, one which Muslims relied on for the better part of thirteen centuries. Unless Muslim lands see a radical structural change that brings their systems of governance in line with the beliefs and values of the people, progress of any form is unlikely in that part of the world.

The Caliphate is thus not only relevant, but arguably the only effective way of dealing with the problems plaguing the Muslim world today in a way that is tied to Muslims’ legal and political tradition. In fact, expecting otherwise and hoping that secular regimes can provide effective governance is indeed a romantic ideal – a “pipe dream.” The supposed neutrality of secularism as a way to organise societal affairs must be challenged, and all the moreso with regards to people who have organised society on an entirely different basis for millennia.

* Shafiul Huq is a student of Islamic Sciences and interdisciplinary studies covering the Humanities and Social Sciences.

[Editors’ note: this article is the first of a series of such articles to address this and associated topics. Please keep an eye out for related future content, Allah willing.]

![]()