In these tumultuous times where Islam and its ideas are being criminalised, one can’t help but wonder what the future holds for Muslims in Australia. Unfolding events as well as historical lessons point to Muslims having to effectively grit their teeth in a new, permanently tense reality. With reference to a seldom-discussed and ugly part of Australia’s recent history, it is high time to ask where this worrying trajectory could possibly lead. Through a look at the concentration camps that Australia operated through World Wars 1 and 2, br Hamzah Qureshi explores this sobering question as the heat rises on Muslims in Australia.

Currently, the Muslim world is engaged in an ever-intensifying struggle against the legacy of western colonial intrusion, and as it marches towards a future determined by its own tradition and norms, will this make the situation even worse for Muslims in the West.

We’ve witnessed raids and arrests within the Muslim community, coupled with the shift towards the criminalisation of Islamic ideas. Could we see a future of complete state mobilisation against Muslims? Large scale arrests, imprisonments, raids or even concentration camps? Surely such things cannot happen in modern Australia?

The fact is that the notion itself is not that out of left field. This sort of thing has already happened – Australia had concentration camps during both World War I and II. This part of Australia’s history is not very well known, but it is attested to by Australia’s National Archives and other government sources which explicitly state:

During World War I, for security reasons the Australian Government pursued a comprehensive internment policy against enemy aliens living in Australia.

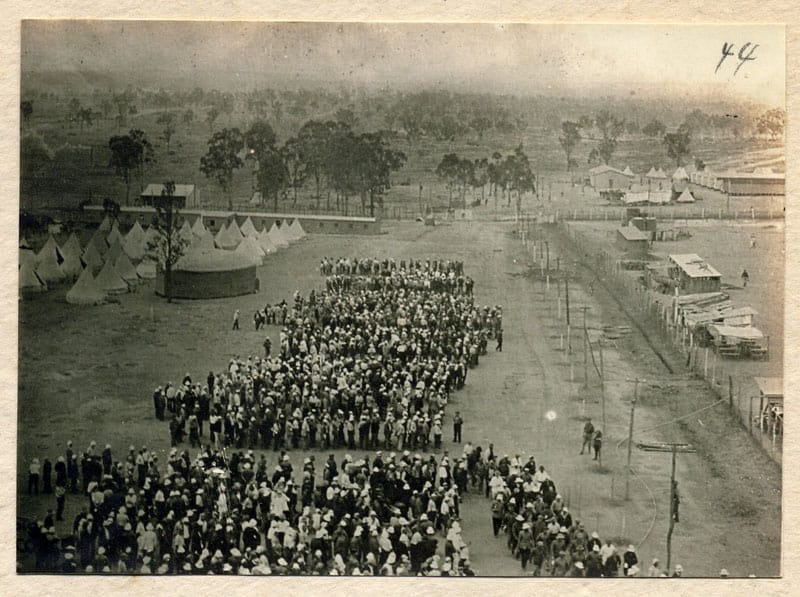

These “enemies” were those born in enemy countries, as well as Australian-born descendants of migrants born in enemy nations. About 7000 people were detained. Prisoners were interned without trial, often without knowing their crime, and without the knowledge of their families. The largest of the WWI camps was in Holsworthy, in the Liverpool region of greater Sydney.

It well and truly resembled a prison, with barbed wire surrounding it and watched over by machine guns and large watch towers. There was solitary confinement for troublesome detainees and regular raids and searches by camp authorities.

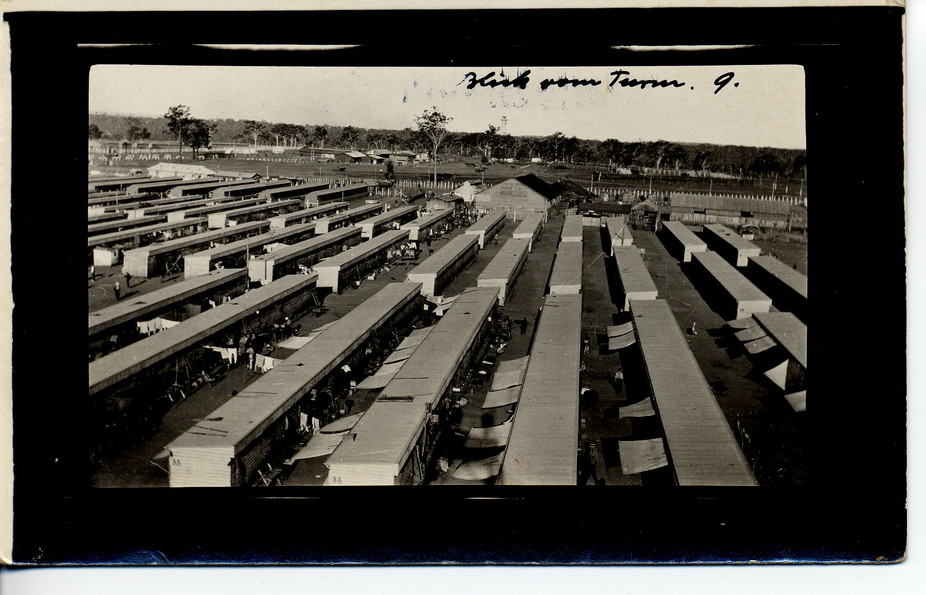

An elevated view of the German internment camp at Holsworthy, looking north and showing the number 3 and 4 compounds.

Holsworthy guards with a machine gun (1916)

During WWII, there were more than 50 camps and one of the reasons for these camps was to appease public opinion. Japanese residents were jailed en masse, as well as Germans and Italians, purely based on their nationality. More than 12000 people were imprisoned. After the wars, most were forcibly deported.

This view from a tower reveals the long rows of huts at Holsworthy internment camp, where Germans were interned during the First World War.

Associate Professor of UNSW tells us the aim of the above-mentioned camps in words that, although referring to camps during WWII, could just as easily apply to Muslims in Australia today:

(The Australian Government sought to…) destroy the (German) community as an autonomous, socio-cultural entity within Australian society…. through many different avenues, the closing of German clubs and Lutheran schools, the internment of the leaders, so as to deprive German-Australians of their spokesmen, their representatives in the mainstream public sphere of Australian society. Together with the destruction of what might be called the socio-cultural infrastructure of the community, this would have the effect – it was thought – of intimidating and keeping in check the rest of the community: it would lead to its disintegration and eventual disappearance.

The internment of “enemy aliens” was a drastic measure, without question, and the lead up to it’s implementation bears striking similarities to what our community endures today. Fischer further writes:

This was a point that was emphasised over and over again: as Lutheran Christians, their allegiance was to the government of the state in which they lived, its institutions and constitutional authority.

The Lutheran pastors were very conscious of their identity as representatives of an Australian, not a German, church. They were subjects of the British Crown and citizens of their respective Australians colonies… It made no difference to them whether individual parishioners had become naturalised or not. Relations with Germany were of a purely private nature, concerning the maintenance of language, family ties and cultural traditions.

The German community were a compliant minority, by any measure. Their belief that their allegiance was to the Australian government was coupled with sincere efforts to conform. Their 102 primary schools taught mostly in English and even their major monthly paper began publishing in English. Despite this, all Lutheran schools were closed during the great war, as were all German clubs and German-language newspapers.

By August 1914, Germans in Australia were forced to report to the nearest police station. They filled out forms which asked for personal information such as name, address, date and place of birth, trade or occupation, marital status, property, length of residence in Australia, nationality and naturalisation details. The police officers would then impose upon them any restrictions deemed fit (such as a a Provisional Order, where the German would have to notify the police of any change of address or to report at daily or weekly intervals) and filled out a second “Report on Person” form, which advised if they found the person in question to be truthful, or whether they were anti-British or consorted with persons of enemy origin. This form ended with a suggestion as to whether or not the individual should be “sent forward for examination by the military authorities”.

“Notice is hereby given that all persons (male and female) who are not British subjects and who are not exempted under the Regulations are required to register in accordance with the War Precautions (Aliens Registration) Regulations 1916”

In this period, the government also passed the War Precautions Act. The Manual of War Precautions contained 81 “offences”, such as measures that forbade “enemy aliens” from possessing motor cars, telephones, cameras or homing pigeons. Fischer states:

In October 1916, the registration regulations were extended to apply to “all aliens, whether enemy or otherwise”. In the end, the machinery of registration, censorship, surveillance, internment and deportation set up by the department to control the resident “enemy” population in Australia was also being used to investigate and prosecute pacifists, unionists, radical socialists, Irish nationalists, anti-conscriptionists of all ideological persuasion – practically anybody who dared to speak out against the government’s commitment to the war.

A precedent was established, involving the use of the state apparatus for the purpose of suppressing political opposition that constitutes one of the ominous features of the political culture first developed in Australia during the war.

We should see in the shutting down of schools, creation of a register, criminilisation of harmless utilities and silencing of political opinions an obvious correlation to the rhetoric and atmosphere of today when it comes to Muslims.

The narrative the Muslim community faces today is that it isn’t doing enough to “fit in”, and that if we conform to the “Australian way of life” we will not be ostracised or targeted (whether by individuals or government policy).

Precedent clearly outlines for us the farcical nature of this narrative – recent history has shown when such measures are implemented things usually only get worse for the targeted community. The people rounded up and detained in the past were not criminals, but people with a certain ancestry or nationality and many times only for the sake of appeasing public opinion (that the government itself helps shape).

Could this treatment be the lot of Muslims in the near future? it is perfectly reasonable to ask what the government may do now to appease current anti-Muslim public opinion, especially when Muslims may present principled political opposition to oppressive state measures. This is a question no one can definitively answer at this stage, but one that most certainly deserves to be raised.

Hamzah Qureshi is a Muslim activist based in Sydney and is a spokesman for Hizb ut-Tahrir. This article is adopted from a talk he delivered at a recent conference in Sydney.

![]()

![Community Protest – Massacre in Myanmar | Sydney Australia [Pics + Video]](https://www.hizb-australia.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/IMG_20170917_121633.jpg)