Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ) said, “The armies of this Ummah will be sent to Sind and Hind” (Ahmad).

Indeed they were sent, and they opened Al-Hind to a subsequent 1200-odd years of Islamic rule in the Indian Subcontinent – a period in which Islam and its adherents made significant religious, artistic, philosophical, cultural, social and political contributions.

The arrival of the Muslims to the provinces of Sindh and Punjab, along with subsequent Islamic sultanates, which overflowed with bureaucrats, soldiers, traders, scientists, architects, teachers, theologians and scholars, played a pivotal role in conveying the message of Islam to the people of the Subcontinent.

“Islam had brought to India a luminous torch which rescued humanity from darkness at a time when old civilizations were on the decline and lofty moral ideals had got reduced to empty intellectual concepts” – N.S. Mehta, in Islam and the Indian Civilisation

ARRIVAL & EXPANSION OF ISLAM IN THE SUBCONTINENT

The first Muslim expedition to the Indian subcontinent was undertaken barely 15 years after the death of the Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ). However, it was not until the year 711CE that Muslims permanently settled in India.

Sailing in the Indian Ocean near the coast of Sindh, the ship of a band of Muslim traders was ransacked and they were taken hostage. The news of this brutal act of piracy reached Damascus, the capital of the Khilafah at the time. The Khalifah al-Walid bin ‘Abdul Malik on hearing about this, sent a message to Hajjaj bin Yusuf, the governor of Baghdad, to demand apologies from the ruler of Sindh, Raja Dahir, and to rescue the Muslims.

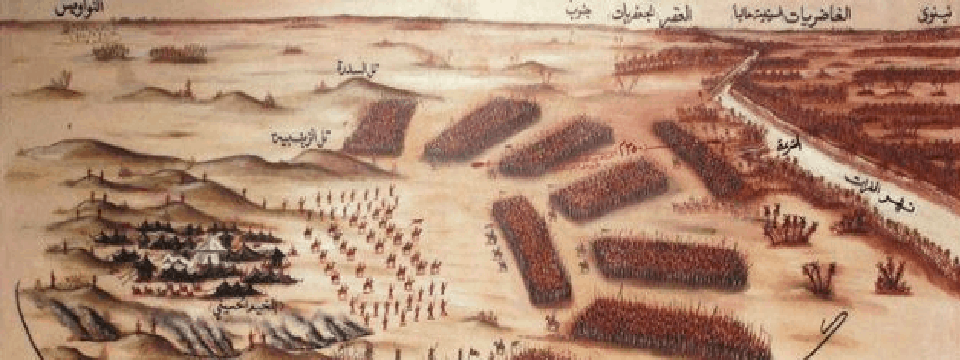

However, the Raja refused, resulting in the dispatching of the armies of the Ummayad Caliphate towards Hind, just as the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) had foretold. Led by one of the most brilliant young generals, Muhammad bin al-Qasim, it was this conquest of Sindh that ushered in the Islamic era in the Indian Subcontinent.

Muhammad b. al-Qasim followed up his initial success with further encounters penetrating into the Sindh towards Multan.

Within three years, by 714, the whole of Sindh and lower Punjab were brought under the rule of the Caliphate. Through these openings, the Muslims brought the area to the light of Islam from the shirk that had hitherto been prevalent. Several local Hindu chiefs and rajas, along with their followers, embraced Islam.

It was during the Khilafah of Hisham b. ‘Abdul Malik from 724 to 743 CE that the Caliphate conquered the regions of Kashmir and Kangra.

During the period of 754-75 CE, under the ‘Abbasi Khalifah al-Mansur, Kandahar was opened, to be soon followed by Gujarat during the Khilafah of Harun ar-Rashid.

Further expansion in Muslim power and influence took place through the historic Khyber Pass in the 10th and 11th centuries by Mahmud Ghaznavi, who ascended to rule in 997. The first task Mahmud undertook after assuming power was to integrate his dominions to consolidate Muslim rule. He invaded India 17 times. The Ghaznavids ruled for more than 150 years and made a significant contribution to the development of Islamic learning. Mahmud himself was a scholar of Fiqh, Hadith and poetry. In spite of his spectacular victories however, Mahmud’s era could not establish a stable Muslim government in India, a feat which was to be achieved first by Shihab al-Din Muhammad Ghauri, who in 1198 triumphantly entered Delhi and made it the capital of Muslim India.

His able successor, Qutb al-Din Aibak extended the frontiers further yet to Benaras and Bengal. Qutb al-Din consolidated the foundations of Muslim presence in al-Hind. The laws of Islam according to the Hanafi madhhab were enforced and customs and practices against the Shari’ah were suppressed. His Islamic reforms won him great acclaim among his contemporaries who hailed him as a true follower of the Khulafa’ al-Rashidin. Aibak tried to acquire the services of the ablest and most learned men of his time, offering the office of Qadi of Lahore to Imam Hasan Saghani, the celebrated muhaddith and linguist.

In the 13th century, Shams al-Din Altumish came to power in Delhi. He founded schools and colleges throughout the land, demonstrating his intellectual interests. He started the tradition of holding academic and religious gatherings at which notable scholars were invited to discuss the Islamic concepts of state and government, with the freedom to express their views and even admonish the Sultan.

Within the next 100 years, what became known as the Delhi Sultanate extended its way east to Bengal and south to Hyderabad. The sultanate was ruled by five dynasties which rose and fell: the Slaves, Khiljis, Tughlaqs, Sayyids and finally the Lodhis.

At around this time, the quest for wealth and power brought Europeans to Indian shores in 1498 when Vasco da Gama, the Portuguese voyager, arrived in Calicut on the western coast. In their search for spices and Christian converts, the Portuguese challenged Arab supremacy in the Indian Ocean. In 1510 the Europeans took over the enclave of Goa, which became the center of their commercial and political power in India and which they controlled for nearly four and a half centuries.

MUGHAL RULE

The last Afghan Sultan of the Lodhis, Ibrahim, was faced with the rising tide of the Hindu-Rajput alliance. It is highly doubtful that the Afghan rulers could have repulsed the tide. This was, however, ultimately done by the great Mughal leader, Zahir al-Din Babur.

Babur was a young and energetic ruler of the Farghanah province (modern day Uzbekistan), and this was neither the first nor the last occasion when the Muslims of the Subcontinent turned to their brothers from Central Asia for help. Babur took Delhi and Agra in 1526. The very next year he succeeded in defeating a huge army of 175,000 men and 1000 elephants brought against him by an alliance of Hindu chieftains. He died in 1530, to be succeeded by his highly educated son, Nasir al-Din Humayun, who gave the Mughal sultanate its first distinctive features.

Described as being extraordinarily lenient by many historians, Humayun is also said to have manifested some distinctly Islamic values in his rule and his personal life. Though many attempts were made at his life, including one by his own brother, Humayun refused the call to avenge, citing the last words of his father, Babur:

“Do nothing (evil) against your brothers, even though they may deserve it.”

Subsequently, and in a very short time, Humayun was able to expand the Sultanate further, leaving a substantial legacy for his son, Akbar, who played a much more significant role in reshaping Mughal administration.

AKBAR: DEVIATION FROM NORMATIVE ISLAM

Akbar ascended to the eminent office of emperor at the age of 13 in the year 1556. Very early on, he sedulously cultivated an interest for and passionately believed in the importance of creating peaceful empire; for him this was the ultimate goal, even greater a priority than the implementation of Islamic norms.

It was during his 55 year reign that life became saturated with passive mysticism, heavily influenced by Hindu philosophy. This proselytical movement away from Islam found its fullest expression in Akbar’s Din-e-Ilahi, which was his idea of the amalgamation of faiths, blending Islam with Hinduism, Christianity, Jainism, Zoroastrianism and other faiths.

But Muslims have always risen to such occasions, as did the scholars of Hind, who after much effort were able to rally Muslims around the true understanding of Islam. Specific mention here must go to Shaykh Abd al-Haq and Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi, the renowned Mujaddid Alf-Thani, or Reviver of the Second Millenium.

This began the revivalist movement in Muslim India which, in many respects, culminated in the ascension of Aurangzeb ‘Alamgir as Sultan in 1658, after Jahangir and Shah Jahan.

AURANGZEB: BASTION OF ISLAMIC RULE

In this respect, his reign is of great importance in the history of Muslim South Asia. Aurangzeb’s indefatigable dedication to the cause of Islam, his strong leaning towards the fuqaha’, and his profound personal piety, bordering on asceticism, have led some Muslim historians to put him in the same category as ‘Umar ibn Abd al-‘Aziz.

The long reign of Aurangzeb delayed the process of the disintegration of the Mughal Empire for several decades, while territorial expansion during his reign was also immense. Even in his old age, he constantly and vigilantly busied himself in combating the multiple historical and social forces working against the Mughal Empire and the Muslim community.

The world-famous Qutb Minar in Delhi, ordered by Qutb-ud-Din Aibak and still to this day the tallest brick minaret in the world at 120m. Its construction started in 1200.

The Badshahi Masjid, Lahore, also commissioned by the great Mughal Sultan Aurangzeb and constructed between 1671 and 1673.

Seldom in human history does one come across a stalwart as circumspectly ambitious as Aurangzeb who fought against a number of heavy odds and succeeded in delaying the imminent downfall of a great Sultanate. He was yet another figure from the many notable ones produced by the great Islamic civilisation founded a thousand years earlier by the best of men, the Messenger of Allah ﷺ.

DECLINE OF ISLAM RULE + COLONIALISM

Sadly though, after Aurangzeb, the decline of the Mughal Sultanate reached it climax. It was a period of general intellectual and spiritual decline amongst the Muslim Ummah at large. The rulers that followed him did not do much to resurrect the situation and in the meanwhile the intellectual and industrial currents garnering momentum in Europe saw the full force of British “modernity” arrive in its colonial guise.

Realising the weakness of the Muslim rulers and emboldened in their own quest, the English decided to explore their options for gaining a foothold in mainland India, and requested the Crown to launch a diplomatic mission. Earlier, in 1615, Sir Thomas Roe was instructed by James I to visit the Mughal emperor Jahangir. This mission was highly successful and Jahangir sent in response: “I have commanded all my governors and captains to give them freedom answerable to their own desires; to sell, buy, and to transport into their country at their pleasure.”

Shah ‘Alam conveying the grant of the Diwani (tax rights from poeple under Mughal rule) to Lord Clive in 1761

Jahangir’s earlier granting of the British East India Company permission to build a fortified factory at the principal Mughal port of Surat was instrumental in the British establishment of an iron grip within the various prominent Indian cities, with Bombay becoming the headquarters of the Company. They employed sepoys (Indian soldiers, trained and led by the British) to protect the trade. However, increased dislocation and the prevalence of cultural indigence, coupled with a collapsing economy, produced a period of great social unrest.

Beginning in the early nineteenth century, rebellions occurred in various areas of the subcontinent, resulting in the 1857 “First War of Independence”. After 85 soldiers were imprisoned for disobeying orders to load their rifles, the remainder of the regiments rebelled on May 10, 1857 and soon much of north and central India was plunged into a year-long insurrection against the British. Despite the extent of the rebellion and the harsh ordeal faced by Indian forces, they were unable to generate a coordinated rebellion, leading to its failure and consequently to the assertion of direct rule through the Crown.

Thomas Macaulay, an English politician said, as he addressed Parliament in Edinburgh in 1859:

“Such wealth have I seen in this country, such high moral values, people of such calibre, that I do not think we would ever conquer this country, unless we break the very backbone of this nation, which is her spiritual and cultural heritage, and therefore I propose that we replace her culture, for if the Indians think that all that is foreign and English is good and greater then their own, they will lose their self-esteem, their native culture and they will become what we want them, a truly dominated nation.”

Though they were successful in achieving this dominance, it was not an easy task. The suppression of Muslims was not left unchallenged. Many of the prominent ‘Ulema issued fatawaa obliging the Muslims of India to not co-operate with the British and that if they could not do this, to make hijrah from India. Meanwhile, developments outside of India had a profound impact on it. This waning of power and the imminent destruction of Islam’s political force threw the Muslims of India into a miserable quandary and confusion until September 1919, when Maulana Muhammad Ali and his brother Shaukat Ali reorganised a band of Muslims and resurfaced in the form of the Khilafat Movement, a pious confraternity whose aim was to use whatever leverage it had to protect the Khilafah.

SEEDS OF REVIVAL: THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT

The fact that the strongest reaction to the Western attack on the Khilafah came from the Indian subcontinent is a point of pride for the Muslims of the region. This mass movement created unprecedented agitation all over the sub-continent.

During the First World War, mosques in India rang with fervent prayers whose khutbahs that would invoke the benediction of Allah for the well-being of the Sultan and the success of his armies in their effort to destroy the forces of Kufr. Conferences were held, as a mass showing of support for the Khilafah. During the Khilafat Conference in 1920, Maulana Azad reinforced the importance of the Khilafah as he declared that “without an Imam, their lives were un-Islamic and that they would be damned after death.”

The ‘Ulama of the time played a pivotal role in not only obtaining oaths from their followers that their lives and hearts would be exerted, by speaking and writing in support of the Khilafah, but also in working tirelessly and with indomitable resolution towards the generation of public opinion for the establishment of the Khilafah. However, as a natural consequence of it being a reactionary movement with no clear methodology, the Khilafat Movement did not last for very long. Unfortunately, the seizure of power in Turkey by the traitor Mustafa Kemal Ataturk on 3rd March 1924 saw the dissolution of the Ottoman Khilafah and saw the movement dismembered.

A day after the abolition of the Khilafah, Muhammad Ali Johar said, as reported by the Times newspaper on 4th March 1924:

“It is difficult to anticipate the exact effects the ‘abolition’ of Khilafah will have on the minds of Muslims in India. I can safely affirm that it will prove a disaster both to Islam and to civilisation.”

With the Caliphate destroyed and the rivalry of the two political forces, the Hindus and the Muslims, reaching new heights, Britain sustained its throttle-hold in the region by capitalising upon their differences. However, with the British Raj struggling after World War II, and being superseded by America as the preponderant global force, could no longer could maintain distant colonies financially and militarily.

Louis Mountbatten was appointed as Last Viceroy of India with the purpose of negotiating the partition of India to form Pakistan and to enact the withdrawal of British forces from India. Eventually the “Independence of India Act 1947” provided the newly formed dominions of Pakistan and India independence on the 14th and 15th of August 1947 respectively.

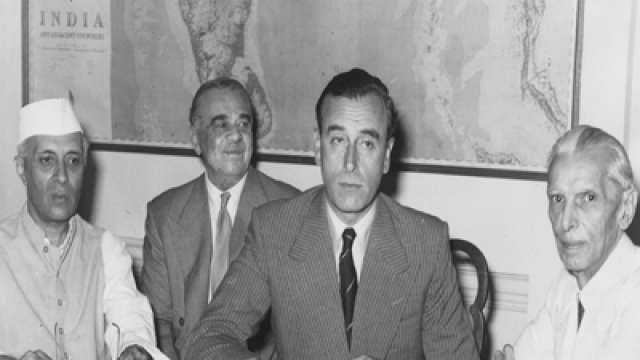

Lord Mountbatten with Jawaharlal Nehru and Muhammad Ali Jinnah at the conference disclosing Britain’s partition plan for India. (Getty Images)

But the British never did give India true independence – it was nominal. They left physically but made sure that their influence remained and specifically made sure that the Muslims of India would not rise again to regain their rightful position in the Subcontinent. They persisted in the instigation of Muslim-Hindu hatred, then, through the United Nations, designated (with some Muslims arguing the same) that those areas which were majority Muslim would form Pakistan and those with majority Hindus would form India, but they did not give Kashmir, a majority Muslim area, to Pakistan, and thus sustained it as a cause of continued division and problems.

‘INDEPENDENCE’

Pakistan was established with the view of the majority that the newly born nation state would be a state based on Islamic principles and composed of Sindh, Baluchistan, Punjab and the areas of the North West Frontier. The aspirations of the people was to see two other areas forming part of the new unified state, namely the Bengali speaking area of Bengal and Kashmir, which had a Muslim majority.

Indeed, Bengal became East Pakistan; however, Kashmir was not to be part of the new Muslim state.

In 1948 Pakistani forces were closing in upon Srinagar, the capital of Jammu & Kashmir, and had they continued they would have unified the Muslim dominated Kashmir with Pakistan, but due to a compromise reached with the UN and India, the early Pakistani leadership called for a withdrawal of troops that led to Jammu & Kashmir forever becoming a disputed area.

Only 2 years after its establishment did Pakistan first taste dictatorship under Field Marshal Ayyub Khan. He was succeeded by Yahya Khan, whose short-lived leadership was followed by the Awami League’s comprehensive win in the eastern region. Pakistan, at the time, was divided into East and West Pakistan. However, political and linguistic discrimination as well as economic neglect led to popular agitations against West Pakistan, whose campaign of suppression, including the discriminatory declaration of Urdu as the official language, led to the war for independence and the establishment of Bangladesh, with the help of India, in 1971.

The seeds for such dissent however were sown much earlier. The first Governor General, Mohammad Ali Jinnah declared to a large Bengali speaking audience in Dhaka, the capital of East Pakistan, that Urdu would be the only state language. Subsequently, local civilian and military rulers resisted this move and continued to implement policies that would call for the breakup of Pakistan.

Political upheaval continued under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who began facing considerable criticism and increasing unpopularity as his term progressed. The bloodless coup which followed saw Zia-ul-Haq take Pakistan into a second military era. Consequently, Pakistan provided a conduit through which the Reagan Government sent financial aid to anti-Soviet insurgencies. For the next 11 years, Pakistan was ruled under civilian governments, yet even then prosperity did not avail. Both Nawaaz Sharif and Benazir Bhutto had two periods in government but they did not contribute much more than corrupt ‘democratic’ regimes.

It is well known that the US will have no reservation in supporting dictators in the Muslim world in order to push for its foreign policy objectives. This was seen when the last civilian government of Nawaz Sharif was ousted in 1999 after his climb down on Kargil was seen as a betrayal of the Kashmiri cause.

On 12th October 1999 the political landscape changed and resulted in the military taking power once again in Pakistan, when Parvez Musharraf, the chief of Pakistan’s military, ordered a coup while sitting on-board a plane.

THE FUTURE

Musharraf’s rule had arguably been the worst for Pakistan since its inception. Musharraf joined with the US in the so called ‘War on Terror’, which was and is seen by people worldwide as a war against Muslims and which had resulted in the arrests and killings of hundreds of Pakistanis. Musharraf had also permitted American forces to establish bases in Pakistan, legitimised the occupation of Iraq, provided logistical support and intelligence to US forces in Afghanistan and surrendered control over Pakistan’s economy to multinationals. There was a growing disparity in income, lack of health and education facilities and general poverty is on the increase. He also effectively submitted Kashmir to India.

Musharraf evidently saw no place for Islam in Pakistan. He sought to promote a ‘moderate’ version of Islam, no doubt at the command of foreign beckoning, which he called ‘enlightened moderation’. His vision for Pakistan was clear in his appreciation of Ataturk and what he did with Turkey.

The political turmoil in Pakistan reached it’s peak when Musharraf declared emergency rule in 2007, and in doing so suspended the constitution. His objectives became clear, in that he desired to cling onto power by whatever means necessary, be it slaughtering the Muslims of Afghanistan and Kashmir, massacring those at Lal Masjid, dismissing the Chief Justice or the heavy monitoring and controlling of the madrassas.

Not much changed when Zardari came into power, nor when we saw the return of Nawaz Sharif. Zardari had a history of financial crime prior to his presidency, and was permissive of para-military operations in Pakistan during his term, evidenced by the Raymond Davis incident. Nawaz’s resumption of presidency gives little hope too, having constant delegations and meetings with foreign powers to “cement relations”, capitalising on rhetoric with promises to move Pakistan forward, giving no self-reflection to the part he plays in a tragic status quo.

What is important for us to realise here is that the continued political disarray in Pakistan is a natural consequence of the interference of foreign powers in Pakistan’s affairs. Though Pakistan was formed in the name of Islam it was to be no more than a secular nation state, forever politically unstable and economically weak.

How ironic it is that the prominent leaders of movement for Pakistan were secular-minded people, raised and educated in Britain. Indeed the first article of the constitution of the All India Muslim League established in 1906 was, ‘to promote among the Mussalmans of India, feelings of loyalty to the British Government’. With such weak foundations, it is little wonder the failure that Pakistan has always been.

24 years under military rule, the rest under civil government. Yet the result always the same: poverty, illiteracy, corruption and crime. The inexcusable tendency of all the rulers of Pakistan to bend to the whims of their foreign masters is the clearest manifestation of their betrayal.

In our revisiting of the history of the Indian Subcontinent in its eras of Muslim and then British rule as well as the subsequent era of ‘independence’, we see nothing less than a world of difference. In this there are great lessons for the Muslims of today. For indeed, it can be no other way. Only when the Muslims of Pakistan execute the Commands of Allah (SWT) and live by Islam, can they be successful, both in this life and the next.

We ask Allah to expedite this state of affairs, and manifest the blessings of Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, and of course Pakistan, again one day soon.

![]()